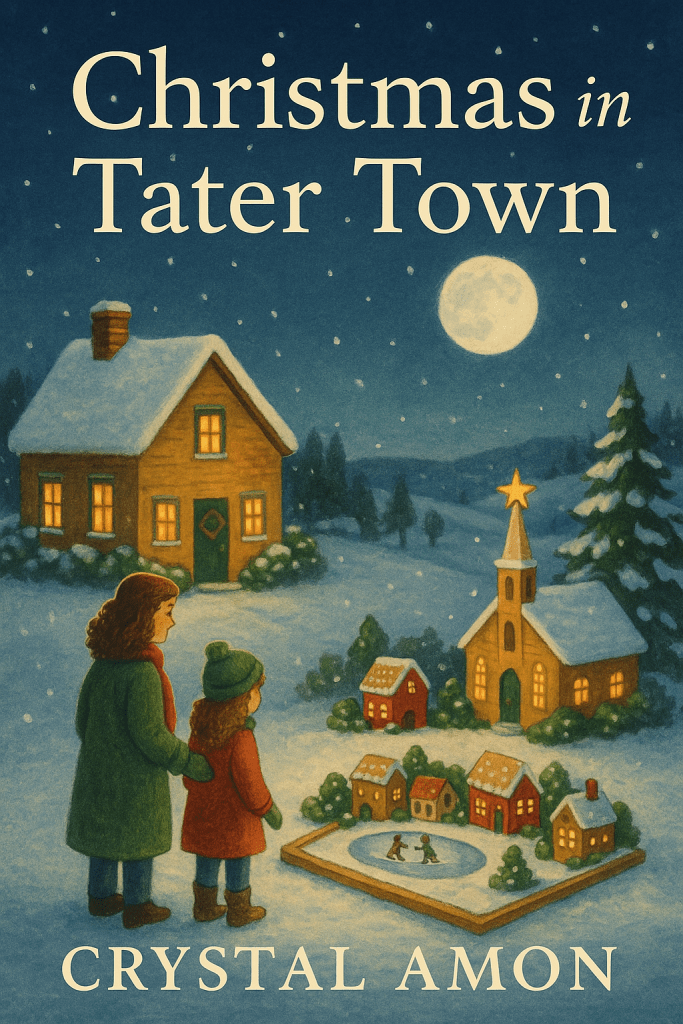

Christmas in Tater Town

The Sugar Map

The snow waited until Christmas Eve to fall, as if heaven were holding its breath over the hills that cradled Tater Town. When it finally came, it came unhurried and sincere—flakes fat as feathers, a slow sift of forgiveness over porch swings and fence rails and the crooked church steeple that leaned like it had a secret. The sign on the highway—WELCOME TO TATER TOWN: HOME OF THE BEST SWEET POTATOES IN TENNESSEE—collected a soft hat of white, and even the rusted tractor across from Aunt Donna’s place looked like it had dressed up for the occasion.

Inside, Aunt Donna’s kitchen breathed cinnamon and orange zest. The oven hummed low, like an old friend telling a quiet story. Imogene stood at the counter, smoothing a ribbon of royal icing along the edge of a graham-cracker roof. Gumdrops gleamed in neat rows. Pretzel sticks waited in a cup like fence posts. A bag of powdered sugar sat open, its dust rising in silvery little clouds every time the bowl was jostled. On the radio, a crackling choir practiced harmonies they didn’t quite catch, which made the song somehow truer.

“Hand me the peppermint shingles,” Aunt Donna said, her voice all pastor’s daughter and pie-contest champion. She wore a flour apron that had seen more Christmases than Imogene had candles on any cake. Her gray hair was twisted into a bun that had given up on being formal somewhere around noon.

Imogene passed the candies without looking. Her attention was fixed on the cardboard base where a tiny town had started to appear—their town, remade sweet: the diner with its stubborn red awning, the post office with a licorice slot for letters, the hardware store that carried everything from nails to sensible gossip. Every year they rebuilt Tater Town in sugar to remember how it fit together. Every year they added something new so the past would keep walking toward them.

“You think the roofs will stay this time?” Imogene asked, knowing they wouldn’t. The roofs never stayed. That was part of the story.

“They’ll behave until the first child breathes on them,” Aunt Donna said. “Which is to say—no.” She glanced at Imogene, reading the face the way she read weather. “Tell me what else you’re not saying.”

Imogene swallowed. Beneath the brightness of the kitchen, there was a quiet ache that had followed her here the way winter follows autumn. Her father had been gone two years, but a person doesn’t stop showing up just because the calendar says so. “I want to add a pond behind the church,” she said. “A skating pond.”

Aunt Donna paused with a peppermint piece halfway to the roof. “For him.”

Imogene nodded. “He used to take me. We’d shuffle along like penguins and he’d pretend he was a ballerina just to make me laugh. He’d say the ice was a mirror that makes time look back at itself.” She gave a small smile. “He was a poet when he wasn’t being a mechanic.”

Aunt Donna set the peppermint down, the old wood table echoing soft. She placed her floury hand over Imogene’s. “Then the town needs a pond,” she said simply. “Christmas is for leaving the light on in the rooms where love still lives.”

They began to build it—crushed blue sugar for water, an oval of clear candy glass fitted into a ring of salt-rimmed pretzel posts. Imogene shaped tiny skaters out of gumdrops and toothpicks: a tall one to be her father, a smaller one to be her. The tall one’s arms were flung wide, ridiculous and brave.

Snow kept falling. The kitchen held them, warm and steady. Midnight approached like a hush you could hear. They set the last piece—a white-chocolate church with a steeple that this year, miracle of miracles, didn’t lean—and stepped back. The model glowed beneath the tree lights, every candy window catching gold.

“You feel that?” Aunt Donna whispered.

Imogene nodded. She felt it. A hum like held breath. A pause that made room for what couldn’t be said. Christmas coming through the cracks.

Town Light

Morning broke pearly and new. The world outside had been made a clean copy of itself: fence rails frosted, mailboxes crowned, the square dressed in white with a scarf of tire tracks. Aunt Donna’s house clicked and creaked as it woke, the heat grumbling through the vents. Somewhere a cardinal scolded the day for being so beautiful.

They loaded Gingerbread Tater Town into a shoebox lined with foil and kindness, then carried it out to the truck along with sweet-potato casserole and a coffee urn that had seen revivals and bake sales and one legendary thunderstorm.

“Seat belt the town,” Aunt Donna said, dead serious. “We can replace casseroles. We can’t rebuild memory on short notice.”

They bounced down the hill into town. Passing the diner, they waved to Earlene in the window—Earlene who had been pouring coffee since the Reagan administration and who could serve solace with a biscuit without breaking eye contact. The wreath on the diner door was too big, nearly swallowing the handle, bow lopsided as a grin.

At the community hall, the line of pickup trucks and hard-used sedans snaked past the steps. Children clomped and slid on the wood floor inside like they’d been issued feet for the first time. The room smelled like cocoa and evergreen and the particular hope that arises whenever people gather with casseroles and reasons to be tender. Paper snowflakes swung from the ceiling on thread, each one too earnest to be symmetrical.

A long table had been cleared by the tree for the town’s sugar self. When Imogene and Aunt Donna lifted the shoebox lid and set the model down, folks shuffled closer as if someone had opened a window to June.

“Look here now,” said Pastor Glenn, peering over his glasses. “You got the water tower this time. And it leans exactly wrong. Perfect.”

“Show me the post office,” demanded little Rosie, whose favorite sport was mailing drawings to herself. “Show me my mailbox!”

Aunt Donna pointed, her voice a soft parade. “There you are, Rosie. Number three. See the little licorice flag? It goes up when love is on its way.”

Imogene ran a last line of icing snow around the skating pond. Lights from the tree brushed the candy surface as if the town itself were bending to look. For a heartbeat—and she blamed the sugar fumes and the lack of sleep—Imogene saw a shimmer in that glass: her father’s reflection, smiling with his eyes crinkled up like folded maps. She blinked and the pond went back to being a pond. But the warmth stayed, the way a handprint stays on a window.

“Good work, kiddo,” the warmth seemed to say from the inside out.

The morning filled with Tater Town things: Mrs. Pike claiming her coconut cake was homemade and everyone politely believing her because grief had taught them that kindness matters more than accuracy; the choir practicing “Silent Night” till the altos found their note; the Johnson boys slipping candy canes into coat pockets like charitable thieves. At noon, Pastor Glenn invited anyone who wanted to share a story to step up to the mic.

Aunt Donna nudged Imogene toward the front. “Say something about your pond,” she whispered.

Imogene shook her head, panic skittering. Grief had made her voice unsure in public; it could lift like a bird or bury itself like a seed. “I’ll sound silly.”

“Likely,” Aunt Donna agreed. “But love endures silliness better than silence.”

The mic stand was a peculiar kind of mercy: too tall for confidence, too short for shame. Imogene cleared her throat, watched her breath ghost the air, and told the room about a mechanic who was sometimes a poet. About Saturdays on skates and cocoa so hot the marshmallows dove for cover. About how a pond could be added to a town even when the pond had mostly lived in two people’s heads.

She finished, blinking hard. The room was quiet. Then hands clapped—awkwardly at first. Not for the speech, which had wandered, but for the space she’d opened where everyone could set their own missing thing down for a minute. People didn’t clap for perfection here. They clapped for the try.

Aunt Donna hugged her, hard enough to be history. “Well done.”

Across the hall, the choir director waved wildly for attention. A snowplow had slid into a ditch out on County Line Road, the driver unhurt but blocking half the lane. The power flickered once, twice, out.

Gasps rose, then laughter. Candles were fetched. Thermoses were opened. Earlene from the diner started pouring coffee from an emergency kettle like a nurse with good gossip. This was a town trained by winters and funerals and harvests: when the lights go, people bring their own.

Aunt Donna leaned to Imogene. “Church has a generator. We’ll ferry the old folks there when the singing’s done.”

“When the singing’s done?” Imogene echoed, amused and baffled. “The lights just died.”

“Exactly,” Aunt Donna said. “That’s when we sing.”

The Errand and the Star

They sang until the hall flickered back to life, lights popping on one string at a time like cautious stars. By afternoon, the roads had been salted and the plow dragged from its shameful ditch. The town’s day rolled on, stitched together from errands and quick mercies: checking on Mrs. Leland’s oxygen machine, hauling wood to Mr. Gates’s back door, knocking snow off the branches that had bent too low over the sidewalk in front of the bookstore that had never quite been profitable but refused to stop believing.

When the hall began to empty for family dinners, Aunt Donna pulled Imogene aside. “One last thing.”

“What now?”

“A star,” Aunt Donna said, looking toward the gingerbread steeple. The tree glittered plenty, but the church roof looked naked, like it had forgotten where to point.

They found the makings of a star in the supply closet: five thin pretzel sticks, a coil of gold ribbon from last year, a bottle of glue, a stubborn roll of tape, and—fortuitous as good gossip—a handful of edible glitter. Imogene held the points together while Aunt Donna wound ribbon around them, then crushed the glitter into the glue like a woman baptizing doubt.

They carried the star carefully, like a new promise, and set it on the church roof. It tilted as if listening. The room’s conversations quieted for an instant—the town’s many hearts catching the same beat—and then resumed with that soft lift of spirit that made even the grumps kinder.

Aunt Donna caught Imogene’s eye. “There.”

“There,” Imogene agreed.

They helped wrap plates for anyone going home alone. They pressed oranges into mittened hands. They packed up Gingerbread Tater Town with the tenderness you loan to fragile things, and let Rosie place a single candy cane at the edge of the pond like a stripe of blessing.

Outside, the snow had settled into a calm that felt like prayer. The day flattened into evening; window after window lit up as if the town were spelling its name in light. As they drove back up the hill, Aunt Donna’s truck thumped over ruts like a tune it recognized. In the passenger seat, the shoebox hummed with quiet pride.

“Remember when your father tried to fix my toaster and turned my kitchen into a sparkler show?” Aunt Donna said, smiling sideways.

“He said the toaster was just misunderstood,” Imogene laughed, shoulders loosening. “He said all machines spoke a language we could learn if we listened at the right pitch.”

“He did listen,” Aunt Donna said. “To people, too.”

They fell into a silence that wasn’t empty. The kind where words are optional because memory has taken the wheel for a while.

At home, the world sharpened to small tasks: boots thumped by the door, wet mittens draped over the radiator, the careful transfer of the town back to its place beside the tree. The lights clicked on in a string, and the skating pond caught them. For a breath, it looked like it was holding stars.

Imogene sat cross-legged on the rug and watched the pond glow. She imagined stepping into that sugar world, toeing the ice with the hesitant arrogance of someone loved enough to be unafraid. Aunt Donna brought two mugs of cider and settled beside her with a sigh that sounded like relief and history.

“You know what your daddy told me once?” Aunt Donna asked. “He said grief is just love with nowhere to park. So you build it a driveway. Maybe a whole road.”

“This is our road,” Imogene said, nodding toward the pond, the church, the silly water tower, the licorice mailbox flag. “It doesn’t go far, but it goes where it matters.”

“Most good roads do.”

The house quieted early. Snow kept its soft conversation with the roof. The clock ticked toward midnight again, slow and faithful. Imogene dreamt of skates carving crescents on a surface that wouldn’t break, of a mechanic humming as he rewired a toaster and somehow lit the Milky Way.

The Knock and the Gift

Christmas morning wore a sky the blue of promises kept. Sun glanced off the snow in clean, almost reckless light. From the kitchen came the dignified sounds of breakfast—bacon considering its purpose, biscuits lifting like gentle applause. Imogene pulled on a sweater and thick socks, then padded to the tree to check that the town had survived the night’s drafts and gravity. It had. The steeple still pointed the way. The pond still held the tiny skaters. The star the two of them had made winked, ever so slightly, with a mischief it must have learned from Aunt Donna.

A knock sounded on the door. Their neighbor, Mr. Corbett, stood on the stoop with a box wrapped in brown paper. He was the kind of widower who fixed everyone’s mailboxes and never admitted to loneliness out loud. He removed his hat, meticulous as church. “Brought you a thing,” he said. “Been meaning to for a year and a half, but meaning to ain’t the same as doing.”

He set the box on the table and opened it like something holy. Inside, nestled in tissue, lay a pair of skate blades—old, polished to a dull shine, the leather bindings oiled and supple. “Your daddy helped me with my Buick the winter after Louise passed,” Mr. Corbett said, eyes off at a distance. “Wouldn’t take a dime. Kept my hands busy and my mouth full of reasons to keep waking up. When he got sick, he told me where he’d put these, said I’d know when to pass them along. I reckon now is the when.”

Imogene touched the leather with a hand that didn’t feel like hers. The blades were heavy and sure, like a promise you could stand on. “Thank you,” she managed, voice small in a room that had grown suddenly big.

“Reckon they’re not for ice,” he said, mouth quirking. “Reckon they’re for remembering you still know how to move.”

Aunt Donna cleared her throat with a sound that wasn’t disdain. “Stay for breakfast?”

“Can’t,” he said, already backing toward the door, like gratitude might startle if handled too directly. “But I’ll expect a review of your biscuits at church.”

After he left, Aunt Donna lifted the blades as if they were an infant. “We could mount them on a piece of oak,” she said. “Hang them where the sun can hit the steel. Let the light do the rest.”

“Or,” Imogene said slowly, feeling a current under the morning, “we could use them.”

Aunt Donna arched an eyebrow. “On what pond?”

Imogene looked at the sugar world, at the gleam the tree lights laid over the candy oval. The ridiculous notion came fully dressed: sturdy boots, a thermos, a dare. She laughed at herself and then didn’t. “Behind the church,” she said, not meaning the gingerbread church at all. “If the creek flooded just right and last week’s freeze did what it meant to, there’ll be a seam of ice in that low hollow. Enough to slide.”

Aunt Donna considered. “Dangerous,” she said, the way people do when their heart is already picking the hat it will wear outside.

“Just a little,” Imogene said. “Like love.”

They ate quickly, which was a crime, and bundled faster, which was an art. The town was already moving—folks in Sunday coats, a neighbor walking a roast to someone’s table, the choir kids in scarves drowning their chins. Behind the church, in the dip where the creek liked to pause, a wash of ice shone like a held breath. It was thin, sure. But at the edges, where the shade had been generous, it had thickened enough to try.

Imogene laced the blades onto her boots with fingers that shook for reasons beyond cold. She stepped to the rim and listened—first to the ice, the way her father taught her. It spoke in small, satisfied creaks. She set one foot down, then the other, knees loose, arms out. The slide wasn’t elegant. It was a friendly shuffle that admitted to gravity but kept the upper hand.

For three minutes or thirty, time came unpinned. Imogene carved slow loops. She laughed after the second almost-fall. She cried in that ordinary, inconvenient way that looks ugly and is secretly beautiful. Aunt Donna watched from the bank, clapping softly after each turn like it was a recital, which—if life is properly viewed—everything is.

When Imogene stepped off the ice, cheeks fevered and eyes bright, the church bell began to ring. A long line of people crossed the hill, small as chess pieces, purposeful as prayer. Without speaking, the two of them fell in step. They’d carry the skates home and hang them by the window later. For now, there was a room to share and songs to mis-sing and a preacher who would probably say one thing that mattered and three that made the babies yawn. They would sit together and be part of a town that had decided, repeatedly, to keep being a town.

Inside the church, candles waited, stubby and faithful. Children rattled paper programs. Pastor Glenn looked a little like he’d slept in his vest, which made the congregation love him more. The choir gathered, all nerves and peppermint. When the opening hymn rose, it did the thing songs do on good days: turned every throat into a window for light.

During the prayer, Imogene felt it again, that felt-but-unseen something. It wasn’t a vision this time. It was a steadiness under the floorboards, a held hand she didn’t grab with fingers so much as with the parts of her that had learned to recognize home when it showed up disguised as ordinary.

She squeezed Aunt Donna’s hand. Aunt Donna squeezed back, one beat extra for I know.

Building Forward

Afternoon came wearing leftover turkey and board games with missing pieces. Snow slid off eaves with satisfied sighs. The day stretched its legs and decided to linger, as if it, too, liked the view from Tater Town.

Back at the house, sun moved slowly across the wall, paused on the skate blades they’d propped in the window, then crossed to the sugar map of their world. The star on the gingerbread steeple threw a tiny glare onto the ceiling, a boast no bigger than a thumbnail. Imogene lay on the rug and watched it pulse as the tree lights blinked.

“What should we add next year?” she asked. It felt bold and right to say next year out loud, to tug the future onto the couch and hand it a plate.

Aunt Donna considered. “The old oak behind the diner,” she said. “Where your daddy carved a heart when he was courting foolishly.”

“He never stopped courting foolishly,” Imogene said, smiling toward the pond. “Even when the toaster was on fire.”

“Especially then.”

They ate pie they weren’t hungry for. They phoned a friend who was lonely and another who pretended not to be. They argued good-naturedly about whether hot cocoa needs peppermint (it doesn’t, but joy often does). They refilled the bird feeder because even cardinals appreciate hospitality.

At some point, Imogene slipped a folded paper beneath the cardboard base of Gingerbread Tater Town. On it she had written three lines in her father’s voice—an imitation at best, but faithful in spirit:

Ice is just water pretending to be sure.

Step anyway.

Let the pretending teach you how.

Evening gathered. Outside, the streets of Tater Town shone under porch lights, little halos laid at eye level. Somewhere, the diner door chimed and Earlene told a story that made the room louder. Somewhere else, a marriage healed a fraction of an inch. A dog found its way home. A widow laughed at something unfunny and felt, for a moment, unburdened.

Imogene and Aunt Donna stood at the window with their mugs, looking down the hill into a town that would never be perfect and would always be theirs. The pond on the cardboard glimmered. So did the idea of the real one, down behind the church, already interrogated by sun and destined to thin. That was fine. Everything thins. Everything thickens. The trick is to keep building.

“You know,” Aunt Donna said, as if handing over a key, “we don’t have to wait for Christmas to add to the town. We could keep it on the table all year. Build a little on Tuesdays.”

“Add the spring fair in March,” Imogene mused. “The watermelon stand in July. The hurricane lamps in a power outage in September.”

“And a pie contest in October where I win by accident,” Aunt Donna said.

“You never win by accident.”

“I always win by accident,” Aunt Donna insisted, which was a lie in service of humility. “We could make room for everything that happens. Even the hard. Especially the hard. I want a gingerbread clinic for the days we need stitches.”

“And a counseling office made of marshmallows,” Imogene said, not missing the point. “Soft on purpose.”

They laughed the kind of laugh that clears a person out. Then they fell quiet, like you do when the inside of the day asks for listening.

Finally, Imogene said, “Thank you.”

“For what?”

“For not trying to fix what can’t be fixed,” she said. “For helping me build around it. For a pond.”

Aunt Donna set her mug down. “Baby girl, I don’t know how to fix anything that involves hearts. But I can sure hold the other end of the ribbon.” She nodded at the town. “And I can bring glitter to a glue fight.”

They turned off all the lights except the tree, letting the room find its night vision. The star on the steeple kept winking. The pond held the reflections it had been given and made them kinder. On the windowsill, the skate blades caught a last piece of sun and threw it right back into the room like a dare.

Snow began again, light as breath. Somewhere a car door shut. Somewhere across town, a baby slept. The world felt temporarily solvable.

Before bed, Imogene slipped on her coat and boots and stepped out onto the porch. The cold reached up and held her face with honest hands. She breathed until her lungs remembered their size. The hill below lay white and familiar, the town tucked in. She thought of her father with his mechanic’s patience and his poet’s stubbornness, his careful listening to the language of broken machines and breaking hearts.

“Good work, kiddo,” the night seemed to say.

“You too,” she answered, to the night and to herself and to anyone who had ever built a road out of a loss and invited others to walk it.

She went back inside and set another log on the fire, then stood for a moment over Gingerbread Tater Town. With a fingertip, she nudged the star a fraction to the left so it pointed exactly where she wanted to go.

“Next year,” she whispered, and then—because love isn’t shy—“and tomorrow.”

The house settled. The tree breathed. The sugar town kept its small watch. And far down the hill, the real town did the same, wrapped in snow, under a sky steady with old light.

Christmas, true to habit, kept coming through the cracks. And the cracks, true to their purpose, let it in.

The End

With love and light,

Crystal Amon

Princess Crystal Says

Copyright 2025

Leave a reply to PrincessCrystalSays Cancel reply